Author: Dava Sobel

Description: A popular science book that tells the story of how a carpenter solved the biggest scientific mystery of his time, revolutionizing watchmaking and seafaring.

Book length: Medium (~180 pages)

Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Introduction

Have you ever heard the phrase ”When Hell freezes over”, ”When pigs fly” or ”Squaring the circle”? Probably yes. How about ”Discovering the longitude”? The last one you likely didn’t hear, but go back a few hundred years, and this expression was used in everyday language to describe an impossible task.

Nowadays we all have GPS on our phones, so we can determine our location very easily and precisely, and we kind of take that for granted. In the 17th and early 18th century however, there was no way of knowing your longitude (how far east or west you are) at sea. As you can imagine, not knowing where you are at open sea is pretty undesirable. Sailors had to rely on estimations (so called dead reckoning) to determine their positions, which was prone to errors due to factors like wind, waves and currents. This could result in drastic changes in course, and consequently to shipwrecking or wandering the ocean for much longer than planned.

So why was such a simple thing like knowing how much left or right you are on the map impossible? And how did a carpenter solve this problem? Luckily for us, Dava Sobel wrote a great book on the topic.

The Longitude Problem – What is the Problem?

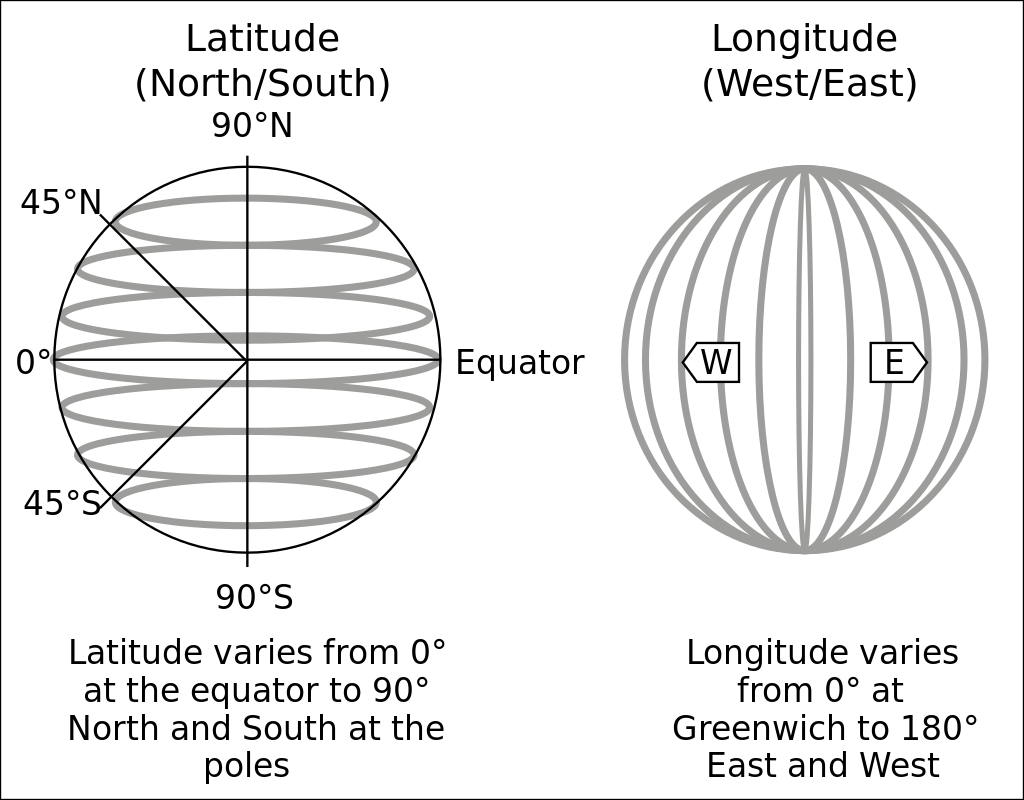

We learned in school about latitude and longitude lines. In simple terms, latitude tells you how far north or south you are, while longitude tells you how far east or west you are on the globe.

Latitude can be figured out rather easily, by measuring the angle of the Sun or some other stars from your reference point. For example, you could measure how high the North Star (Polaris) is on the sky from your position. Right on the North Pole, Polaris is directly above your head (90 degrees). If you walk now down towards the Equator, Polaris would appear to be lower and lower on the sky, until it would sink right at the horizon when you arrive at the Equator (zero degrees). So if you observe how high Polaris is on the sky, you know how much north or south you are. Easy enough!

So why is longitude such a big problem? Why is it so much harder to figure out how much east or west you are? The answer is kind of obvious when you think about it: the Earth is spinning in that direction. So the Sun and the stars are moving across the sky in the same direction as you travel! This means that you can’t use their position to figure out how much you have moved in that same direction. You can think about it like this: if you start your journey to the west exactly at noon, and move in such a way that the Sun is always directly above you, it would be noon for you all the time! Without a timepiece you would have no way of knowing how much time has passed from the start of your journey. So our key word here is: timepiece!

The Longitude Problem – Clocks

Ok, so the Earth spins. We start to travel east or west. The Sun also travels east to west. What now? How to solve this? That was the unsolvable problem for hundreds of years. Even minds like Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, or Christiaan Huygens did not manage to solve it. There is however a simple method you can use in theory, which was known even to the ancient Greeks – and it involves knowing the time. If you know for how long you travel, you also know how far you travel. A little math (don’t worry, it’s simple):

It takes the Earth 24 hours to make one full rotation (1 day).

One full rotation is 360 degrees.

This means that in 1 hour, the Earth spins 360/24 = 15 degrees.

So a 1 hour difference equals 15 degrees of longitude difference.

This means that if at any point of your journey you knew your local time (can be easily deduced by looking at the Sun), and the time at a fixed location (looking at a clock you brought with you), you could calculate how far east or west you have traveled.

For example, say go to open sea from Lisbon. At some point on your journey you want to see where you are. You figure out by looking at the sun that is noon. Then you look at your clock you brought with you from Lisbon where it says it is 3 P.M. in Lisbon. Now you know there is a time difference of 3 hours between Lisbon and you, which means you moved by 3×15 = 45 degrees of longitude. Makes sense?

And there we have it. If you know the time at two places, you can find your longitude! You just need to have a clock…the problem was there simply did not exist a clock which was accurate enough to do the job.

The Prize Money

In the book, the longitude problem is first presented a bit more generally, with examples why it is important. Not being able to navigate properly meant that sometimes whole warships were lost in wreckages, with thousands of people loosing their lives. We also have to remember that this was the time of expansion of great powers in the world. Whoever had the better ability to navigate their ships, had an edge in establishing their power at sea (trade routes and colonies). Empires of the time offered large sums of money to anyone who could provide a feasible solution to the problem. The British established a special committee, called The Board of Longitude ” and offered a prize of 20 000 £. This might not seem that much, but adjusted for inflation, this would be between 4 and 5 million pounds in today’s money. So basically, if you present a feasible solution to find longitude at sea, you go home a millionaire. Not bad, huh? This just shows you how important this was to the great powers of the time.

Some really bizarre solutions are mentioned in the book. But basically it came down to 2 realistic options: either you use the sky which would involve special tables with recorded data of stars and moon phases, coupled with complex calculations, or you make a sufficiently accurate clock.

John Harrison

And now we come to John Harrison, a man working as a carpenter who built and repaired clocks in his spare time. Before he was twenty years old, he built his first pendulum clock, even though he never received any formal training as a watchmaker. The clock was almost entirely made out of wood. He continued to make improvements, creating several more wooden clocks. As if building an entire clock with no training wasn’t impressive enough, additionally the clocks kept nearly perfect time. They drifted no more than a second in a month. In comparison, the best clocks of the time drifted by more than a minute a day. That is insane!

When Harrison heard about the longitude prize, he was confident enough in his watchmaking ability to try to create a timepiece for the competition. The big challenge in creating a clock to be used at sea are all the rough condition it needs to withstand. Changes in temperature, humidity, the rocking motion of the ship, etc. All those things meant that regular pendulum clocks of the time would either gain or loose too much time, or even stopped working altogether. So Harrison had to invent some new clockworks…and he did!

The first one he built was named H1, which you can see on the image below. It kind of looks more like a time machine than a clock. After finishing it, Harrison felt he could do better and made 2 more improved versions, H2 and H3, all of which you can still see clicking in the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

Those clocks could already secure him the prize, but he still wasn’t pleased. After gaining some new ideas and experiences, he figured he can produce an even better watch in a much smaller size, and so he created H4 (image below), one of the most important watches in history.

This was the watch that would ultimately win the Longitude prize, but not without some drama. Remember the other option of calculating longitude using the starts and phases of the moon? Well, turns out that some important people in the Board of Longitude tried to get the prize themselves. And them being astronomers, they did not like a mere mechanical watch to triumph over the night sky. What followed was sabotage, changing terms of the contest, additional demands, and even the involvement of the king himself! But for that you will need to read the book 😉

At the end H4 proved to be accurate in real life conditions, and the impressed captains seeing it in action quickly ordered one for themselves. No one could deny the masterpiece Harrison created, so he secured the prize and helped secure Britain’s naval dominance at the time.

Writing Style and Structure

In terms of form, I think this is a very good structured popular science book. It has 15 quite short chapters, which I thought were divided well. The language and writing style seemed very fluent to me. I thought the author made a good job getting the science points across, while also writing some additional interesting stories surrounding the topic. The main protagonist is still Harrison, but you also get an idea about the topic as a whole, and the general quest for solving the longitude problem.

My edition (the cover from the beginning) has a large font size, yellowish pages, and the perfect size for carrying around – also helps that it is quite light.

Regarding the subject matter, it is rather aimed at people with interest in popular science, so if you don’t find this topic interesting at all, you’ll probably want to skip this book. If you are willing to give it a chance, I think there is enough interesting material to satisfy the ”non-enthusiast” as well. In any case it should be a quite easy read.

Graphics Not Found

The biggest issue I have with this book is that there are no illustrations or maps. One of the main things you read about are John Harrison’s timepieces, and at no point can you actually see how they look like. I thought this was very disappointing. Not using illustrations and maps probably made the book more affordable to produce, and I get that. Still, when talking about navigation, meridians, and complex clock mechanisms, I think you have to include some kind of illustrations to make it a bit more clear.

It’s true that we can check out the images and videos easily enough on our phones (something I recommend you do if you’ll read the book), but this should come as an optional addition. Not a deal breaker, but definitely something I felt was missing.

Conclusion & Verdict

Longitude is a great popular science book. It gives us a background on an interesting topic and tells the story of how it all unfolded. The book is well structured and nicely written. I think it gets all the points across really good, and adds enough context to completely understand the story of discovering the longitude. The only thing that is desperately missing are some illustrations or images of the clocks that are so much talked about.

I would probably not recommend this book to everyone. However if you have some interest in history or just find the topic cool, I think you won’t be sorry for reading it. Plus it is quite short and won’t take too much of your time.

I am really glad this book exists. It’s easy to forget how big of task something was back in the day, when now we have it readily available. Seeing someone be persistent and motivated to do something difficult (even considered impossible) and then actually succeed in that is truly inspiring. If you are interested in the topic, there is a fun video explaining it in short, or if you are really interested there is a full 1h documentary, covering almost everything from the book.

After many years of fighting mainly with himself to create the best watch possible, Harrison had this to say about his prize winning watch:

”I think I may make bold to say, that there is neither any other Mechanical or Mathematical thing in the World that is more beautiful or curious in texture than this my watch or Timekeeper for the Longitude . . . and I heartily thank Almighty God that I have lived so long, as in some measure to complete it.’‘

The best thing about this quote is – he was right.

Rating: 4/5

Pros

+ Interesting topic, an inspiring true story

+ Nicely structured and written

+ Not too long, easy to read

Cons

– No illustrations or images of the clocks which are the center point of the book